Due to their reliance on artistic mastery, funding, labor, and most importantly a significance associated with national ideals, monuments in Thailand prior to the 1932 Revolution were primarily constructed by the state to glorify the nation's fundamental institutions under absolute monarchy. These monuments included statues of past kings, sculptures of high-ranking royals, memorials commemorating the deeds of kings, and even statues of the king's beloved dog (Ya Le), and more. The 1932 Revolution did not only usher in an era of democracy and equality, but also a shift in artistic and architectural styles, alongside new meanings for monuments. A prime example of this is the statue of Thao Suranari, erected in 1933 by the People's Party. This was the first monument commissioned by the new government, and is also the first to honor an ordinary, commoner woman in Siam.

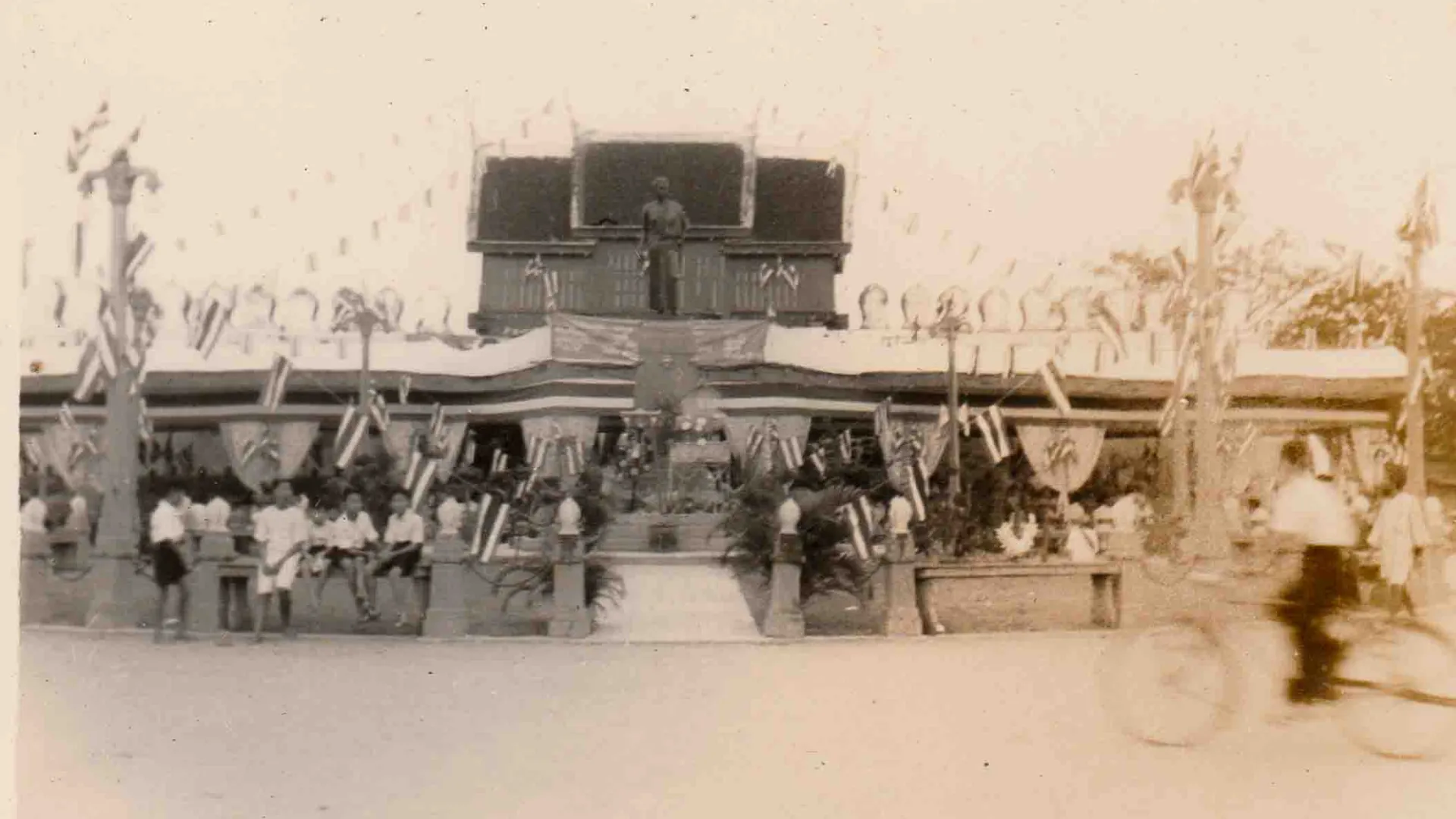

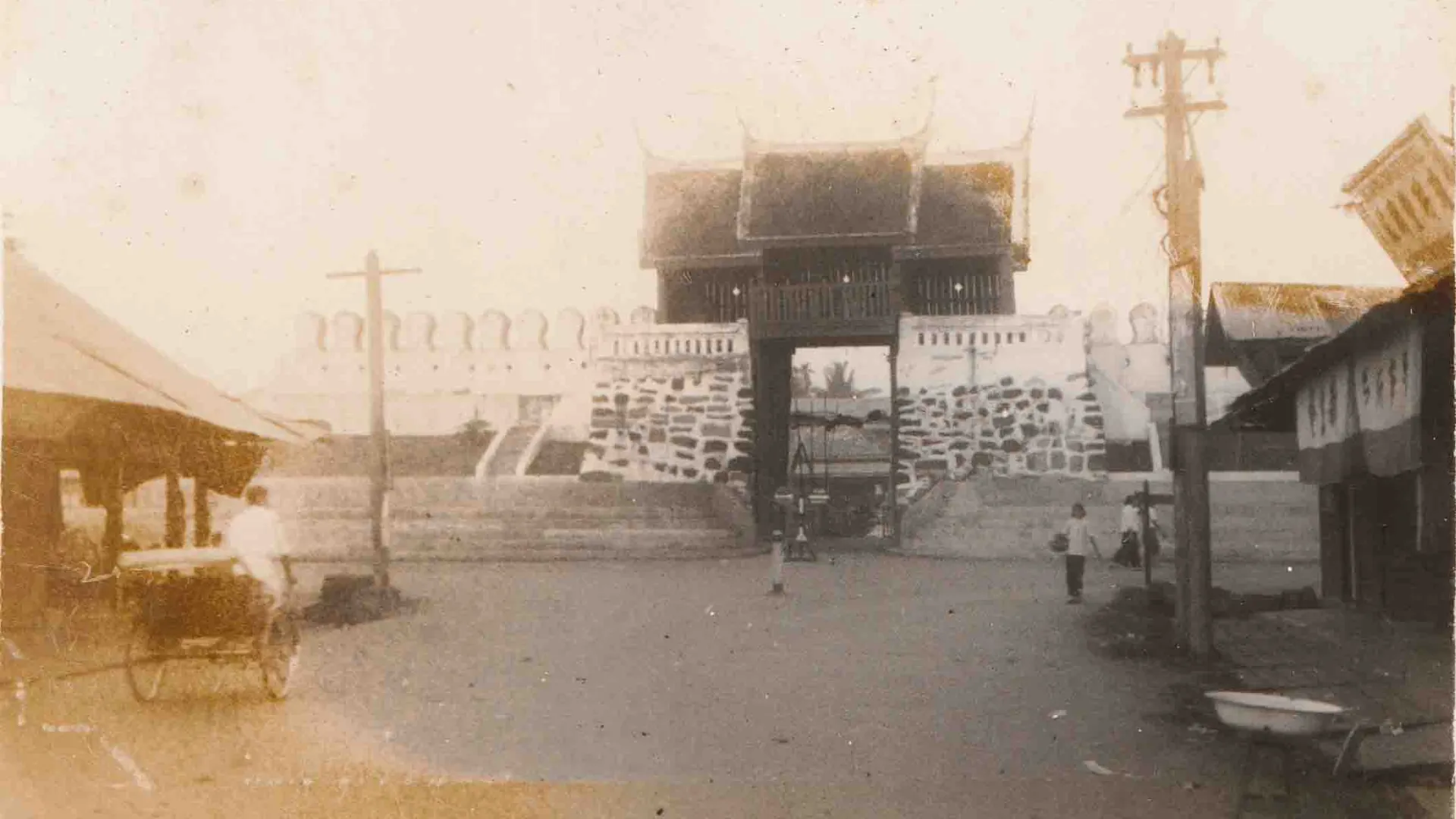

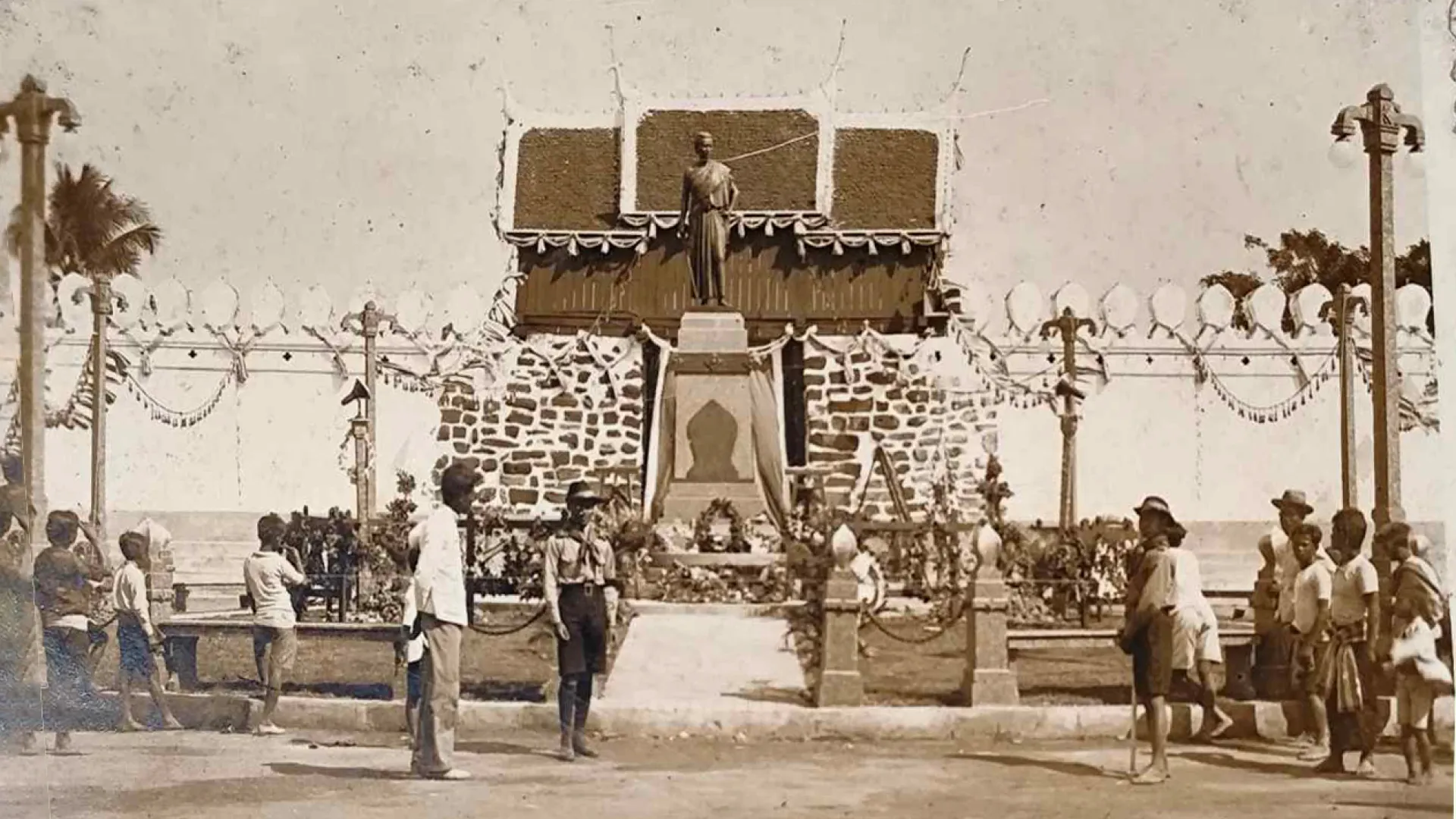

The Thao Suranari Monument, also known as the Ya Mo Monument, stands proudly at the front of Chumphon Gate (the western gate of Nakhon Ratchasima City). Designed by Silpa Bhirasri and Phra Thewaphinimmit, the monument commemorates Thao Suranari (Ya Mo), a commoner woman who played a pivotal role in defending the city against the invasion of Chao Anouvong of Vientiane. While her story is recounted in just three lines of the Rattanakosin Chronicles of King Rama III's reign, and there is no concrete historical evidence to confirm the veracity of the event, Ya Mo's status as a commoner resonated deeply with the People's Party's modern nationalist ideology, which placed the people at the forefront of national development and advocated for gender equality, aligning with the ideals of civilized nations. The monument itself is a testament to this shift. Crafted from blackened bronze, it stands 185 centimeters tall and weighs 325 kilograms. The sculpture depicts Ya Mo in a realistic style, her body proportioned and standing upright. Her right hand rests on her sword, and she is devoid of any insignia that would indicate high status. This stark contrast to the traditional approach to monument building, which often portrayed the subjects as divine-like figures. The erection of the monument also stemmed from the desire of the people of Nakhon Ratchasima to have a symbol that embodied their patriotism. This was particularly significant given that their hometown had served as a stronghold for Prince Boworadet's forces in the "Boworadet Rebellion", aimed at restoring power to the monarchy. Since its completion, the Thao Suranari Monument has become both a new landmark for the city and a unifying symbol for the people of the province.

The Thao Suranari Monument stands as a pivotal symbol in the transformation of societal perceptions regarding the role of ordinary individuals. By immortalizing a commoner woman from history in the form of a monument, the statue challenged the notion that ordinary citizens were mere subjects in the absolute monarchy. Instead, it emphasized their active participation in shaping the nation's destiny under the new democratic regime. The choice of Nakhon Ratchasima, a provincial city, as the location for the first such monument further reflected a shift away from the centralized development model that focused solely on Bangkok. However, the decline of the People's Party's influence in the aftermath of 1947, coupled with the resurgence of royalist sentiments, gradually obscured the historical context of the monument. This, in turn, influenced the public's perception of the Thao Suranari Monument, transforming it from a monument of equality into a sacred symbol of spiritual worship. Despite this shift, the monument's central location and the story of a commoner fighting for freedom have continued to draw political significance. The surrounding area has become a frequent gathering place for political rallies, particularly during the 2009-2010 Red Shirt protests and the anti-dictatorship demonstrations of 2020-2021. In this way, the Thao Suranari Monument has once again reclaimed its connection to the political ideals of the People's Party.