While death is an inevitable part of life, the cremation practices prevalent in Siam before the 1932 Revolution posed a significant and enduring challenge for commoners. The traditional method of cremation involved open-air pyres constructed using brick, mortar, or wooden logs to support the body, with firewood stacked around it. This rudimentary approach not only presented an unpleasant sight for passersby but also created severe environmental and health concerns for surrounding communities. The cremation process would also often involve multiple bodies simultaneously, necessitating the storage of corpses prior to the ceremony. This practice was fraught with issues, as bodies were often stored in makeshift structures that lacked proper fencing, or temporarily buried in shallow pits. The resulting stench and the risk of animals scavenging the remains posed significant health hazards. According to data from 1935, there were upwards of 2,400 corpses stored in makeshift shelters around Bangkok, with over 2,700 temporarily buried, awaiting cremation. These alarming figures would inevitably have an adverse effect on the well-being of the capital’s residents.

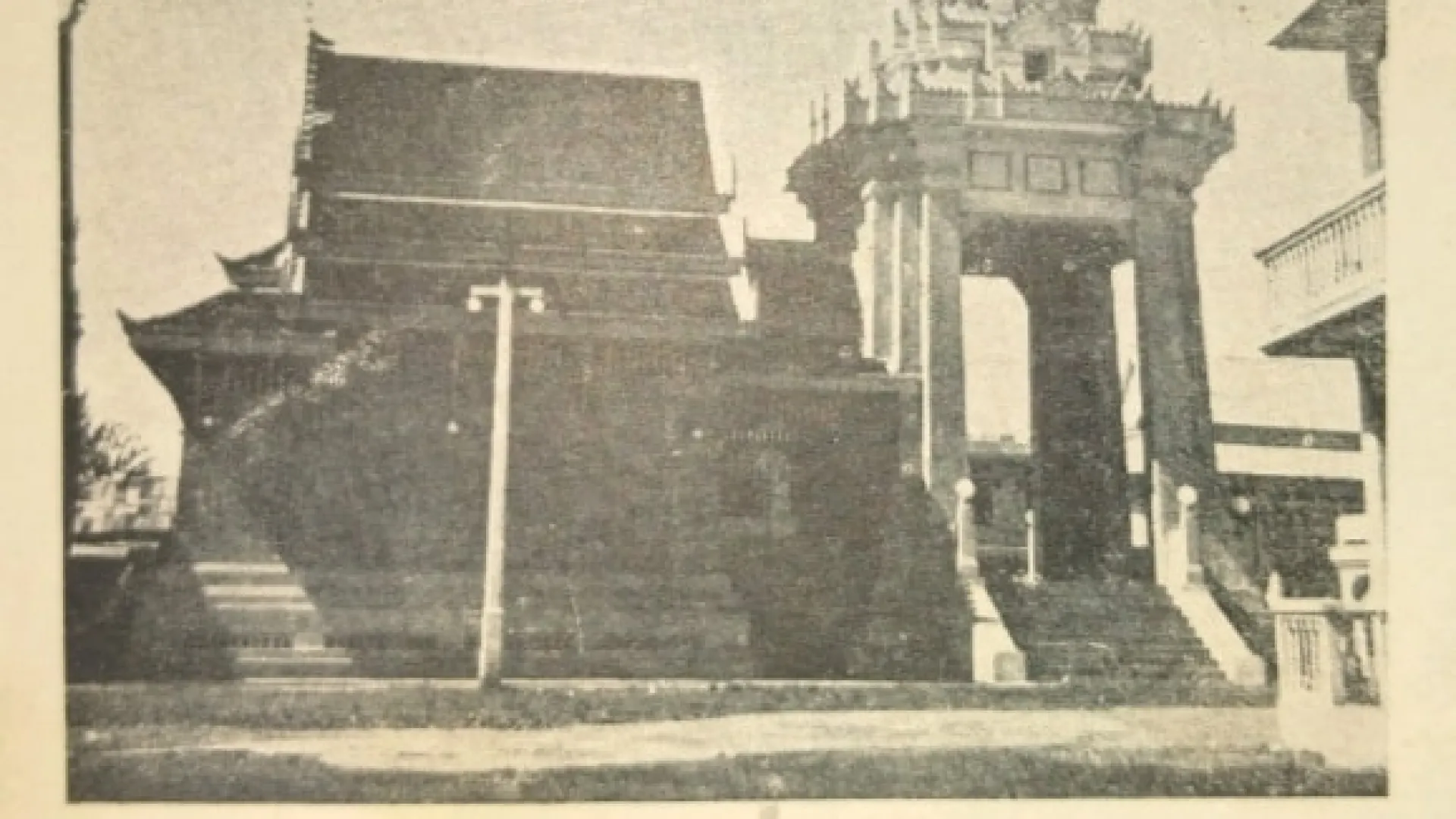

Despite the importing of modern crematoria from abroad as early as the reign of King Rama V, these facilities were reserved for royalty and upper class people, as family members were reluctant to have their loved ones cremated alongside those of lower status. The cremation of individuals from lower social classes continued to take place on traditional open-air pyres. Under these circumstances, in the aftermath of the 1932 Revolution, the People's Party recognized the need for more sanitary cremation practices for common people. In 1935, the "Committee for Planning the Location of Cremation Facilities" was established, headed by Luang Praditmanutham (Pridi Banomyong) and presided over by Phraya Borirakwetchakan, Director-General of the Department of Public Health. The committee initiated a pilot project to construct a permanent crematorium on a 7-rai plot of land near the Sao Thong Fort, Pak Khlong San, Thonburi. The site was to include a guest house, crematorium, modern incinerator, and a hygienic morgue. The proposed design featured an Art Deco architectural style, considered highly modern at the time. Unfortunately, the project was halted due to budgetary constraints. The decision was made to establish a public organization to oversee the initiative, and the Bangkok Cremation Limited Enterprise Act of 1936 was drafted. However, this plan also fell through. It was not until 1940 that the first permanent crematorium for common people was finally constructed and opened at Wat Traimit Witthayaram Worawihan. Designed by Phra Phromphichit, a Thai architect from the Fine Arts Department, the crematorium featured three main sections: a front hall in the shape of a traditional Thai building with a Mandapa-style roof, a modern incinerator building at the rear, and a connecting roof between the two structures.

The opening of the first public crematorium at Wat Traimit in 1940 marked a pivotal moment in Thailand's public health system. This facility not only gained immediate popularity but also served as a model for the construction of crematoria across the nation, a trend that continues to this day. The unpleasant odors and unsightly scenes associated with the traditional open-air pyres were significantly reduced. The popularity of the Wat Traimit crematorium led to the complete cessation of open-air cremation at Wat Sa Ket, the largest cremation site in Bangkok, in 1947. Most importantly, the crematorium emerged as a powerful symbol of equality. Regardless of one's social standing, their remains could now be cremated with dignity and respect. While the Wat Traimit crematorium was demolished in 2007 to make way for the temple's new Maha Mandapa, its legacy endures as a testament to the transformative power of the 1932 Revolution. The persistent issue of cremation in Thailand stemmed not from a lack of appropriate technology but from the class-based discrimination practiced by the families of the elite, who were unwilling to have their loved ones' remains mingled with those of commoners.